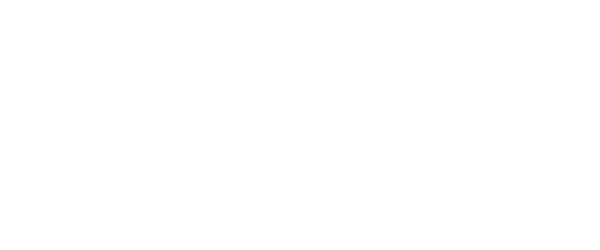

This plaque commemorates the author James Plunkett, author of Strumpet City.

Find this plaque on Google maps.

James Plunkett Kelly was born in Sandymount, Dublin, on 21 May 1920. He was educated at Synge Street CBS, and, following the death of his father, became a clerk in the Dublin Gas Company. There he joined the Workers’ Union of Ireland (WUI), becoming a union official and working alongside James Larkin.

During the 1950s, Plunkett became a regular contributor of talks, short stories and radio plays to Radio Éireann, which he joined in 1955, eventually becoming the head of RTÉ’s features department in 1968.

His first published was ‘The mother’, which appeared in the The Bell in 1942, and many other works followed, including the play ‘The risen people’ in 1959.

Plunkett’s best known work is Strumpet City; published in 1969 it sold over 250,000 copies worldwide and was translated into several languages. Paperback rights were bought for £16,000 and the seven-part dramatisation of the novel, adapted by Hugh Leonard and screened by RTÉ, is regarded as one of the highpoints of the station’s dramatic output.

Strumpet city was followed by Farewell companions (1977), a semi‐autobiographical account of Dublin life between the 1920s and 1940s, and The circus animals. Neither achieved the success of Strumpet city, though some critics thought Farewell companions superior. In 1987 he published a collection of essays, The boy on the back wall.

James Plunkett died on 28 May 2003.

Veteran Dublin City Councillor Mary Freehill, who was friendly with the Kelly family, proposed that the plaque be erected. It was unveiled on 21 May 2024 at 25 Richmond Hill, Rathmines, on what would have been his 104th birthday.

You can read more about James Plunkett in the Dictionary of Irish Biography.