Dublin City Council unveils a commemorative plaque to the Irish language writer Seosamh Mac Grianna, at the site of his home in St Anne’s Park, Raheny.

Born in Donegal in 1901, Mac Grianna came from a storytelling background, and his brother Séamus Ó Grianna was also an Irish-language author.

Trained as a national school teacher in St Pat’s, Drumcondra, Mac Grianna was a staunch republican, took the anti-treaty side in the Civil War, and was interned in Newbridge camp.

In 1924 he began writing as Gaeilge and during 1924–5 he contributed many of his early short stories, including ‘Teampall Chonchubhair’, ‘Teacht Cheallaigh Mhóir’, and ‘Leas ná Aimhleas’, to the newly founded An tUltach. These later formed the basis of his first book, ‘Dochartach Dhuibhlionna & sgéalta eile’ (1925).

He also contributed numerous articles to a range of publications, including the Irish Press. Although his active literary career only lasted around eleven years, he made a significant contribution to the development of literature in the Irish language, publishing ten original works, translating twelve books into Irish, and also publishing a substantial number of reviews and letters.

Four particular books stand out within his body of work: An Grádh agus an Ghruaim (1929), An Druma Mór (1935/1969), Mo Bhealach Féin (1940), and Dá mBíodh Ruball ar an Éan (1940).

In the main, he ceased writing after 1935; in his own words “Thráigh an tobar” – the well dried up. Around this time, be began to suffer from psychiatric illness, which afflicted him for the rest of his life.

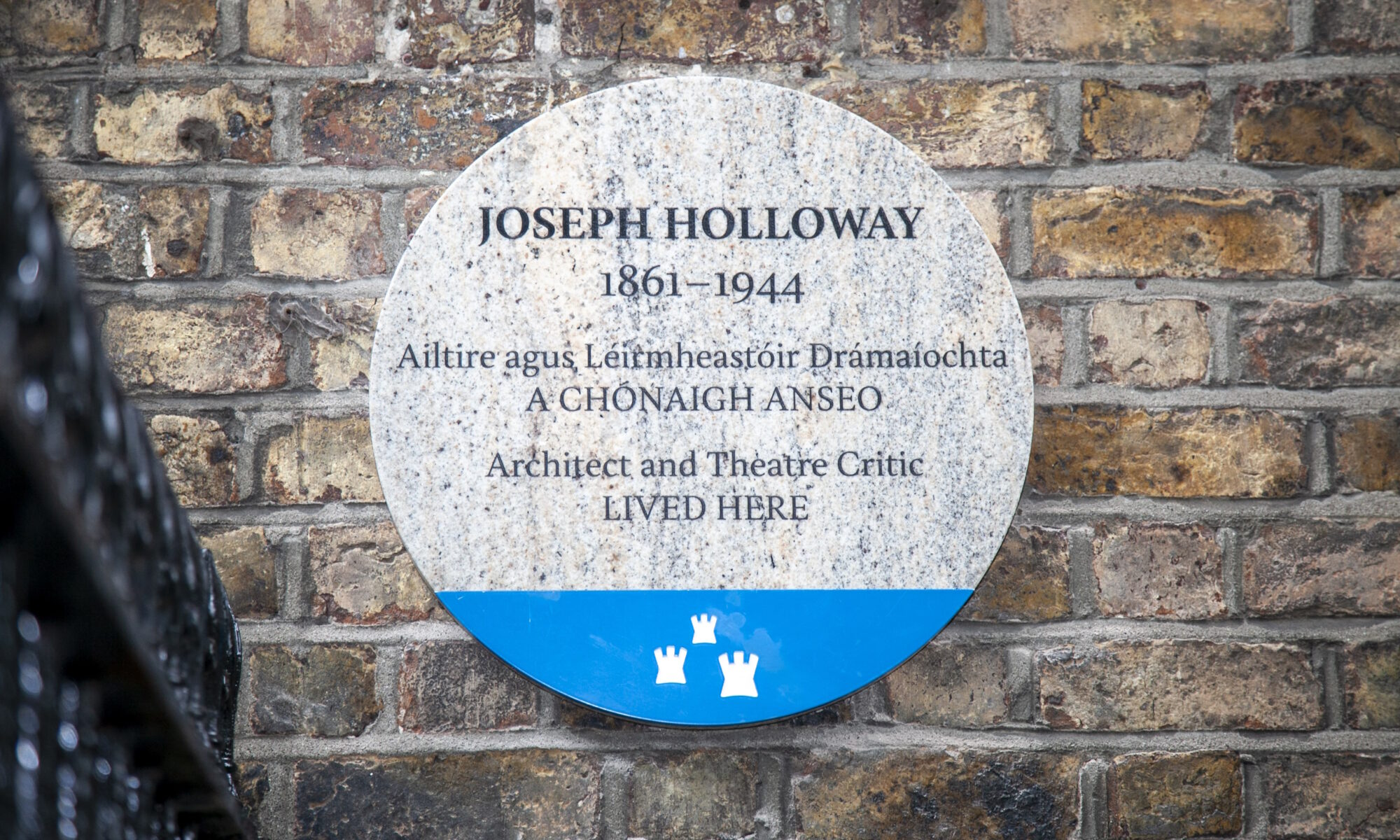

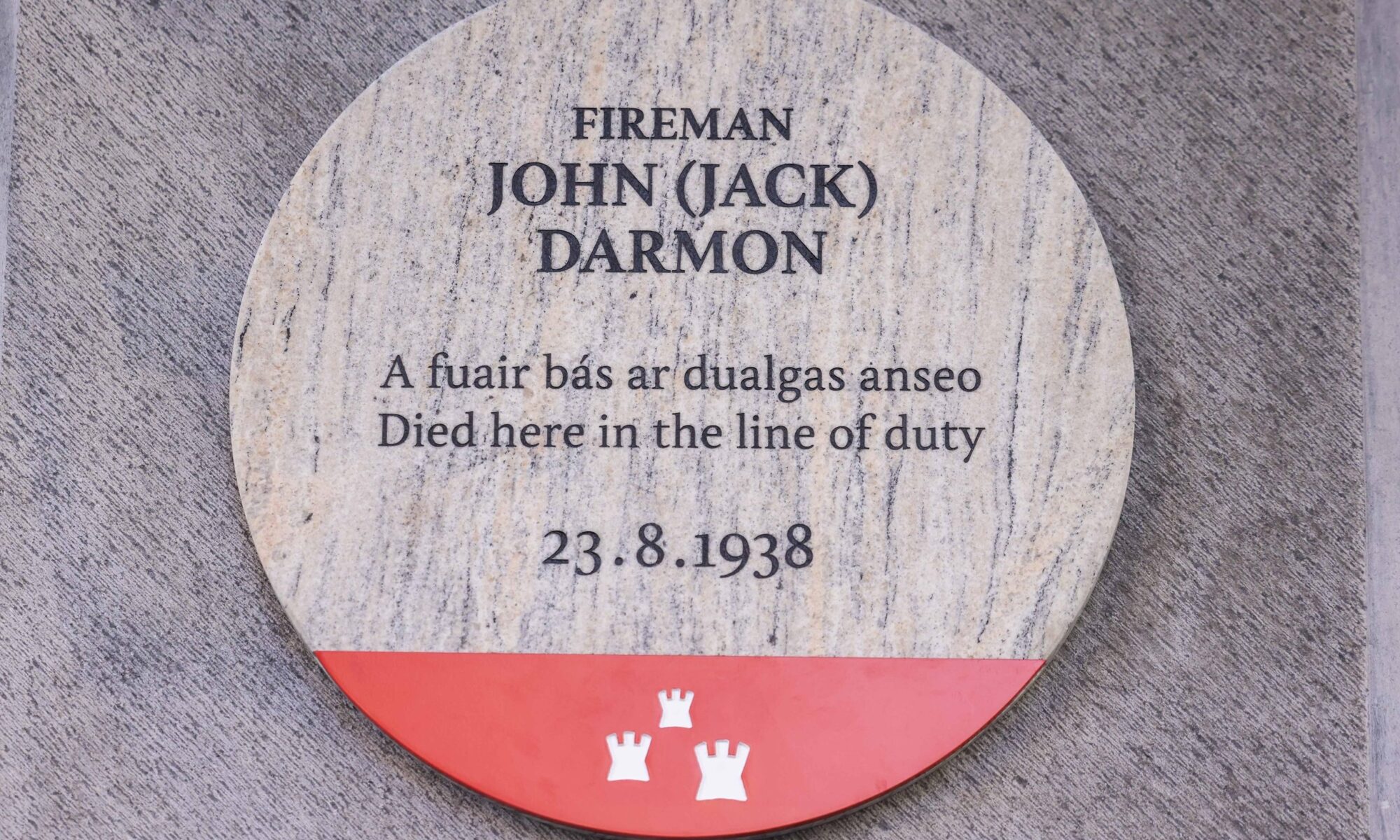

Mac Grianna lived in Dublin through the 40s and 50s, moving from place to place. Sometime around the early 1950s, he settled in a house on the coast road, in St. Anne’s Park, near Watermill Road. The commemorative plaque is erected on one of the remaining gate pillars of the house.

Speaking at the unveiling Cllr Donna Cooney, representing the Lord Mayor, congratulated the local Ciorcal Comhrá Raheny group who proposed that the plaque be erected, saying “comhgairdeas to the members of the Irish language group in Raheny who have ensured that someone who lived in our area and who contributed to the culture and artistic life of our City will not be forgotten.”

Also speaking at the unveiling was Proinsias Mac an Bheatha, whose father knew Mac Grianna: “Nuair a bhog Seosamh Mac Grianna isteach sa sean tí, laistigh de Pháirc Naomh Áine, ní raibh sé ag tabhairt aire dó féin. Bhí m’athair, Proinsias Mac An Bheatha, ag cónaí congarach leis i gCluain Tarbh. Mar sin thosaigh sé ag tabhairt roinnt airgid agus bia mar chabhrach dó ó am go ham. Bhí an-mheas ag m’athair air mar scríbhneoir agus dúirt sé liom go minic gur saghas James Joyce é don teanga Gaeilge.” (When Seosamh Mac Grianna moved into the old house within St Anne’s Park he was not looking after himself. My father, Proinsias Mac An Bheatha, was living nearby in Clontarf. He therefore he started to bring money and food to help him from time to time. My father often told me that he considered Seosamh Mac Grianna as the James Joyce of the Irish language.”)

An tOllamh Fionntán de Brún, who has written about Ma Grianna said “Bhí Seosamh Mac Grianna (1900-90) ar dhuine de mhórscríbhneoirí Gaeilge an 20ú haois, scríbhneoir a shaothraigh stíl dhearscnaitheach phróis nár sáraíodh go fóill. Baineann na blianta a chaith sé i gCluain Tairbh leis an taobh tragóideach dá shaol. Is mór is mithid an t-aitheantas seo a thabharfar anois dó sa phlaic chomórtha” (Seosamh Mac Grianna (1900-90) was one of the most important Irish writers of the 20th century whose indelible prose style has never been surpassed. The tragic aspect of his life is inextricably linked to the years spent in Clontarf. The commemorative plaque is a timely and most welcome recognition of those years.”)